By Gary Phillips

The children at Paterson Public School Number Five could see no trace of the stars that used to shine on the other side of Liberty Street.

For more than two decades, the students only witnessed negligence when they looked at Hinchliffe Stadium through their classroom windows. Shattered glass littered the National Historic Landmark. Trees grew over not only the bleachers, but also a rich tapestry of Black baseball history and other vibrant parts of Paterson’s past. Graffiti obscured the walls, as well as a shameful chapter of America’s story.

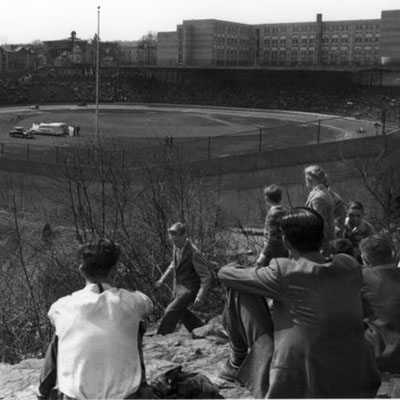

Take one glance at Hinchliffe Stadium since it was abandoned in 1997, and it’s hard to imagine that Negro Leagues icons graced the grass that gave way to cracked pavement. The likes of Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Cool Papa Bell, Buck Leonard, Martin Dihigo and Oscar Charleston—barred from Major League Baseball due to their skin color—all journeyed to Hinchliffe. Orange High School graduate Monte Irvin and Paterson’s own Larry Doby played there before becoming MLB legends. Doby, who died in Montclair in 2003, became the first Black player in MLB’s American League in 1947, just months after Jackie Robinson broke MLB’s color line in the National League.

“It’s been fallow for 25 years. You’ve got generations of Patersonians that don’t know anything about it,” Paterson Mayor André Sayegh says of Hinchliffe. “All they know is it’s a decrepit stadium. It’s in disrepair. They’re like, ‘What is that? It’s an eyesore.’ And it’s more than an eyesore. It’s where history happened.”

All that history lay in ruins until April 14, 2021, when a $94 million repair project broke ground at Hinchliffe. The long-awaited redevelopment plan includes a multisport youth athletic facility, a restaurant and event space, affordable senior housing, a preschool, parking, and exhibitions dedicated to Hinchliffe’s hallowed heyday, which spanned from the 1930s to the 1980s.

And maybe, just maybe, it will bring an MLB game to a site that once provided Black ballplayers with a home when the segregated league wouldn’t—if Sayegh and local baseball stars get their wish.

***

Perhaps that thought sounds preposterous at first. After years of decay, Hinchliffe’s makeover isn’t expected to be finished until late 2022. Once complete, its field dimensions and seating capacity, roughly 7,500 people, will be small by MLB ballpark norms. Accessibility to the stadium and parking are also potential problems for a large game.

But MLB’s special Field of Dreams Game between the Yankees and the White Sox, which was played next to the Iowa cornfield where the iconic baseball movie of the same name took place, quelled similar concerns in August 2021. That game’s ballpark held about 8,000 people and featured short corner-outfield fences. The nostalgic contest was a cash cow for MLB; its tickets were the most expensive ever for a regular-season game, and it was the most watched regular-season game since 1998.

That undisputed success gave an ex-MLB player and current broadcaster an idea. “The one I’m pushing for is Paterson, New Jersey. It’s one of the last standing Negro Leagues ballparks,” Harold Reynolds said on MLB Network the day after the Field of Dreams Game, referring to Hinchliffe Stadium. “I would love to have a Major League game put on there.” Reynolds, a Montclair resident, declined to be interviewed for this piece.

Sayegh, who wants Hinchliffe to host an MLB game as soon as 2023, says that Reynolds plans on broaching the subject with MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred. Sayegh tells us that he has also discussed the idea of the game with former New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, who is on the Mets’ Board of Directors. Sayegh says Christie told him that he would talk it over with Mets owner Steve Cohen. Christie declined to comment to New Jersey Monthly.

Sayegh wants a potential MLB game at Hinchliffe to be a matchup between the Yankees and the Mets. He envisions them wearing the uniforms of the New York Black Yankees and the New York Cubans, two Negro Leagues teams that called Hinchliffe home.

“This will also tell the American story and major league story of integration. It’s a story that probably wasn’t told and some people didn’t want to tell. But now we have a unique opportunity,” Sayegh says, reciting his sales pitch to MLB. “This is a real field of dreams, with all due respect… They never really played on that field. This is where history happened.”

But Brian LoPinto, president of Friends of Hinchliffe Stadium, a group that advocates for the site, says that 2023 may be “unrealistic” for an MLB game. After attending the Field of Dreams Game, he estimates that an event at Hinchliffe would require a year of planning. It would also need features not typically seen at a youth facility, which Hinchliffe is becoming, such as larger locker rooms and infrastructure for broadcasting and instant replay. However, LoPinto is confident that Hinchliffe can host a “world-class event” if MLB, the city, and the Paterson school board, which owns the stadium, align.

MLB has not dismissed the possibility of playing at Hinchliffe. The league plans on returning to Iowa this year for a second Field of Dreams Game, and it has recently held games at other unique locations such as Fort Bragg in North Carolina, the College World Series in Omaha, Nebraska, and the Little League World Series in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, in addition to international series.

“We were delighted by the overwhelming fan response to our 2021 event in Iowa,” MLB wrote in a statement to New Jersey Monthly, “and we hope to highlight other special locations with rich baseball traditions in the future, as we have since 2016.”

***

In 1981, 34 years after Robinson and Doby integrated MLB, 18.7 percent of the league’s players were Black. However, that number dwindled to 7 percent in 2021.

“You’ve got kids right here at home who want to play baseball,” says Trenton native Al Downing, the first Black pitcher in Yankees history. “But the facilities aren’t there, the equipment is not there, the wherewithal is not there, the coaches are not there. The Little Leagues are not there. So kids gravitate toward other sports.”

While many would argue the league is playing catch-up, MLB has recently taken steps to highlight and promote baseball in the Black community. MLB designated the Negro Leagues as major league in December 2020 and committed up to $150 million to the Players Alliance, a group of players seeking to create opportunities for the Black community in baseball and society, in July 2021. Minor League Baseball, meanwhile, announced a new national community outreach platform this past February 1, the first day of Black History Month.

A game at Hinchliffe Stadium would further MLB’s goal by sharing baseball’s Black history with a wide audience while appealing to future generations. While MLB is not making any commitments yet, Reynolds and Sayegh’s concept sounds like a home run to some members of the league’s fraternity.

“It could inspire some young African-American kids to aspire to play in the big leagues. That would be wonderful,” says Larry Doby Jr., whose Hall of Fame father played high school football and baseball at Hinchliffe before being discovered by the Negro Leagues’ Newark Eagles. “It’s been a long-standing thing that there has been a disconnect, and MLB is certainly trying its best. This would just be another example, maybe, of something that could connect that community with Major League Baseball.”

“That would go down as one of the greatest accomplishments that MLB has ever done,” adds former Mets and Yankees pitcher Dwight Gooden. A former Jersey resident, Gooden joined Sayegh, Doby Jr. and New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy at Hinchliffe for an event about Paterson’s redevelopment in December 2020.

Ex-Mets general manager and current team ambassador Omar Minaya attended the groundbreaking last April. “I’m hopeful that, someday, this will come to fruition,” the Bergen County denizen says of an MLB game at Hinchliffe.

Sayegh thinks such an event would be Paterson’s equivalent of the Olympics. Whether his city gets such a spectacle remains to be seen, but Hinchliffe’s story will be told either way.

***

In addition to courting MLB, the mayor wants the renovated stadium’s exhibits to serve as an annex to the famed Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. Sayegh has been in contact with the museum’s president, Bob Kendrick, who is “overjoyed” that Paterson is protecting what he calls “a substantial Negro Leagues artifact.”

“We couldn’t be more excited about this effort to save that historic stadium and keep alive the ghosts of Monte Irvin and Larry Doby and all the others who played in that venue,” Kendrick says. “We should never forget those, as my friend Buck O’Neil would say, who built the bridge across the chasm of prejudice.”

Robinson and Doby deservedly receive credit for the construction of that bridge in baseball. However, many laid the foundation before they crossed it. The likes of Bob Gibson, Willie Mays, Henry Aaron and Ken Griffey Jr. became MLB greats after the sport was integrated, but countless Black players never got that chance.

“My father always said he wasn’t the best [player]; Josh Gibson was by far,” Doby Jr. says of the Negro Leagues. “But he and Mr. Robinson were lucky enough to get the opportunity, and they made the best of it and opened the doors for people to come behind them. Showing the spotlight on those guys who didn’t make it to the big leagues, giving them just due, and making sure that their history is preserved legitimizes what they did.”

The exhibits at Hinchliffe will do just that, with or without an MLB game. But Sayegh knows an assist from the league would certainly help tell this story.

“It’s very realistic. I think it’s got legs,” he insists. “The racial consciousness has been aroused, right? We’re talking more about race relations. We’re having more candid conversations about what has happened in the past, what’s going on in the present, and what we’d like to see happen in the future.

“Restoring Hinchliffe Stadium, that’ll play a role in continuing the dialogue around race relations, how far we’ve come, and how we’ve got some more to go.”